In recent years, public concern has grown over the presence of heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and arsenic in everyday foods, including some popular snacks and baked goods. When people are presented with headlines alerting them to the idea that routinely consumed foods, such as Girl Scout Cookies, might contain heavy metals, it causes them to worry. But to truly understand what this information means, including understanding any realistic human health impact that might be related to such products, it’s essential to distinguish between the concepts of hazard and risk. These are two terms that are often confused but critically different in the fields of exposure sciences, toxicology, risk assessment, and public health. Using the example of Girl Scout Cookies and citing a recent study which claims that Girl Scout Cookies contain elevated levels of heavy metals and glyphosate, RHP Risk Management demonstrates the importance of not only distinguishing between hazard and risk, but the importance of appropriate risk communication for public health awareness.

In the realm of public health, a clear understanding of the distinction between hazard and risk is essential for informed decision-making. A hazard refers to any agent or situation that has the potential to cause harm, while risk is the likelihood that this harm will occur under specific conditions. This distinction forms the foundation of risk communication—the process of providing information about potential hazards and associated risks to make informed, independent judgements about risks to health, safety, and the environment. Without this clarity, there is greater potential for confusion, misinformation, misinterpretation, and ineffective responses to public health challenges.

How Do Heavy Metals End Up in Our Cookies?

The metals referenced in the Moms Across America study are not intentionally added as an ingredient in Girl Scout Cookies, rather they are trace contaminants that arrive in our pantries via several different pathways. Most commonly, many metals occur naturally in the earth’s crust, and when grown in metal-rich soils grains such as wheat (which is often used as an ingredient in cookies) may take up those metals through their roots. Groundwater or surface water may also naturally contain metals, which can contaminate irrigated crops. Further, human activity can play a part in metal contamination of our food supply. Industrial activities such as mining and smelting can release metals including lead, arsenic, and cadmium into nearby soil and water and airborne industrial emissions can settle onto farmland and crops.

Analyzing the Risks Associated with Girl Scout Cookies

Using the same approach taken in a previous RHP-authored blog where we discussed concerns in the media surrounding the use of chlormequat chloride in commercial agriculture, we analyzed a recent study conducted by non-profit group Moms Across America, which concluded that Girl Scout Cookies contain “extremely concerning” levels of heavy metals and glyphosate. In our analysis, we provide context to the study findings by comparing the numbers against established regulatory standards, such as those set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In the above referenced study, laboratory analysis reported “one hundred percent of the samples were positive for glyphosate” as well as “one hundred percent of the cookies contained at least 4 out of 5 heavy and toxic metals, aluminum, arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury.” Collectively, scientists may refer to these as “chemicals of concern” (COCs), which are substances that have been identified for their potential to harm human health. Regulatory agencies, such as those discussed above, establish oral reference dose (RfD) values for COCs. An oral reference dose provides a framework for assessing the potential risks of exposure to COCs; it is a toxicity benchmark, and its purpose is to define a threshold exposure below which no adverse health effects are expected, even for sensitive individuals. Typically, an oral reference dose is expressed as “mg/kg/day” or milligrams of a substance (COC) per kilogram of body weight per day. If a person’s estimated exposure to a COC is below the respective oral reference dose, the probability of that exposure causing adverse health effects is considered low. Reference dose levels are firmly grounded in robust approaches and rely upon rigorous scientific data while incorporating and accounting for substantial factors of uncertainty. These factors of uncertainty directly or indirectly address dietary patterns, an individual’s health status, duration of exposure, and quality and quantity of supporting scientific evidence amongst many others. These reference levels are fundamentally defined as the maximum amount of chemical one can be exposed to each day over a lifetime.

Understanding COC thresholds is essential to effective risk management and regulatory compliance, and it is a cornerstone of sound risk communication; enabling stakeholders to determine whether a substance’s presence actually constitutes a meaningful health risk.

Applying Scientific Concepts to Cookies

When reviewing the Moms Across America study claims against Girl Scout Cookies, RHP evaluated the study’s findings against the established oral reference doses for the relevant COCs (in this case heavy metals and glyphosate) using exposure metrics and maximum concentrations of the detected heavy metals and glyphosate. Exposure metrics are parameters used to quantify estimates of the COC an individual is exposed to over a period of time. The comparison between an oral reference dose and the exposure metric is often called a margin of safety (MOS) which indicates how much higher a known safe level is compared to the actual or estimated human exposure.

Which Cookies were Identified in the Study?

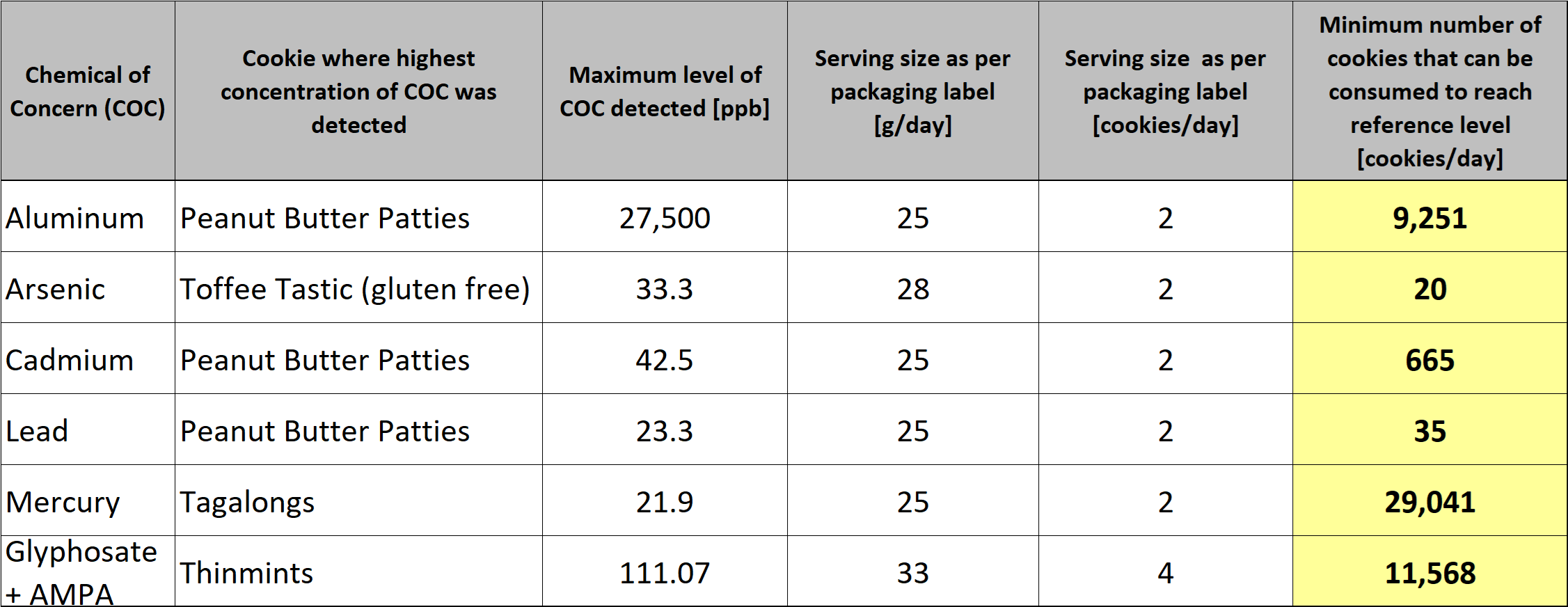

In the table below, RHP identified the maximum levels of COCs that were detected for each Girl Scout Cookie in the Moms Across America samples. As a reminder, the COCs addressed included heavy and toxic metals (aluminum, arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury), and glyphosate.

Contextualizing the Numbers

The Moms Across America study reported “one hundred percent of the cookies contained at least 4 out of 5 heavy and toxic metals, aluminum, arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury.” The study further claimed “76% of the cookies tested positive for levels of cadmium that exceeded the EPA limits in water, and 96% of the cookies contained lead.” These values represent the first step of a thorough risk assessment, which is the identification of a hazard. As discussed previously, this is only one part of the risk assessment process. The crucial next step is to analyze the risk; to assess the likelihood of a harm occurring based on the hazard that was detected. As is the case here, the detection of a hazard does not automatically mean there is a risk present.

To demonstrate this idea, RHP performed a risk analysis for each of the heavy and toxic metals reported in the Moms Across America Study by comparing the values of COCs identified with their respective oral reference dose to determine the MOS (margin of safety). As stated earlier, the comparison between an oral reference dose and the exposure metric is often called a margin of safety (MOS) which indicates how much higher a known safe level is compared to the actual or estimated human exposure. The analysis indicated the following:

- To exceed the oral reference dose for aluminum, a 70 lb. child would have to eat a minimum of 9,251 Peanut Butter Patties cookies per day for a lifetime.

- To exceed the oral reference dose for arsenic, a 70 lb. child would have to eat a minimum of 20 Toffee Tastic gluten free cookies per day for a lifetime.

- To exceed the oral reference dose for cadmium, a 70 lb. child would have to eat a minimum of 665 Peanut Butter Patties cookies per day for a lifetime.

- To exceed the reference dose for lead, a 70 lb. child would have to eat a minimum of 35 Peanut Butter Patties cookies per day for a lifetime.

- To exceed the reference dose for mercury, a 70 lb. child would have to eat a minimum of 29,041 Tagalong cookies per day for a lifetime.

Further, the Moms Across America study reported, “Thin Mints with the highest levels of glyphosate (99 ppb).” To exceed the oral reference dose for glyphosate, a 70 lb. child would have to eat a minimum of 12,925 Thin Mints per day for a lifetime.

From the table, one can see that there is a striking difference in the number of cookies that can be consumed if the heavy metal concentration is the basis. For instance, one can consume up to a minimum of 20 Toffee Tastic gluten free cookies per day if arsenic is your concern or in the case of lead up to 35 cookies per day of Peanut Butter Patties. Although not expected, the allowable quantities are quite large for metals such as aluminum, cadmium, and even mercury. Such stark differences beg a deeper understanding of the exposure metrics but more importantly the oral exposure reference doses.

While discussing dose, it should be noted that reference dose levels based upon drinking water consumption, as were cited in the Moms Across America study, involve a vastly different calculation than oral consumption of cookies over a short duration in a typical year and does not necessarily constitute an “apples to apples” type comparison.

Why is the Reference Dose Different for the Different COCs?

An oral reference dose is different for each substance because it reflects the unique toxicological profile, potency, and health effects of that specific substance.

For example, in comparing lead and aluminum, lead is highly toxic, especially to the nervous system and even at very low levels. Lead exposure can cause developmental neurotoxicity in children, cognitive impairments, cardiovascular issues, and kidney damage in adults. Lead has tremendous bioaccumulation and retention potential, meaning it can accumulate in bones, brain, liver, and kidneys, and it can remain in the body for decades. In contrast, although aluminum can be potentially toxic at high doses, it is generally less acutely toxic and most healthy individuals with normal kidney function can excrete aluminum efficiently. Accordingly, the U.S. EPA and CDC recognize no safe blood lead level which drives a much lower oral reference dose for lead. The oral reference dose set by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) is much higher because there are minimal effects at certain exposure levels in animals or humans.

What Does it All Mean?

Simply put, our health and the health of others should always be a priority and making a meaningful effort to understand what we are feeding our bodies and helping others understand the same is both admirable and advisable. But when it comes to food safety, both hazard and risk assessments are essential. Regulatory agencies use evaluation of hazard and risk to set standards, monitor food supply chains, and protect the health of consumers. Before we move our treasured sleeves of Thin Mints from the freezer into the garbage and declare Girl Scout Cookie season a public health emergency, its important to take a pause and carefully consider the concepts of hazard vs. risk; to differentiate between trace “contamination” and trace “danger.” If Girl Scout cookies are on your favorites list, you can continue to enjoy the occasional Peanut Butter Patty, because, in the words of the Paracelsus, father of toxicology, “All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.” Eating thousands of cookies per day is a dietary practice that most certainly presents other more concerning adverse health outcomes than consuming a maximum daily allowable level of metals or herbicides.

For more information on RHP’s toxicology services, please contact Ashish Jachak, PhD, MBA; Frank Pagone, PhD, CIH; or Ben Heckman, MPH, CIH, and visit rhprisk.com.